You’re invited.

On this coming Monday, May 8th, we’ll be hosting the extraordinary designer - and brand new AIGA Medalist - Lance Wyman for a lunch and conversation at COLLINS in our New York City office in Greenwich Village.

We have a few extra seats if you’d like to join us.

Wyman has been recognized for decades for his mastery of visual ecosystems and for setting the standard for the universal, public design experience: “Out in the street” is more than a mantra for Lance Wyman.

It’s an organizing principle that has driven him to ride alongside beat cops in downtown Detroit, discussing the finer points of crowd management with museum security guards in Washington D.C., and interviewing bartenders in Mexico City—all in an effort to illustrate a specific place through design. His designs for metro stations, zoos, museums, and international sporting events have established him as a model public designer. “Lance has nearly always worked for a mass audience, yet has not had to dumb down his design,” said Adrian Shaughnessy, one of the editors of a monograph on Wyman’s work published in 2015. “That is some achievement.”

Born on July 2, 1937 in Newark, New Jersey, Wyman grew up in nearby Kearny, a traditionally Scottish neighborhood. He learned how to tell stories from his grandfather, and his mother encouraged him to draw.

Following a tip from a friend of his father, he went to study industrial design at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. While there, he became interested in designing an image that could communicate an idea in a systematic and spatial way: a universal, visual language. His first experience of this sort was designing graphics for the American Pavilion at the 1962 Zagreb International Trade Fair in Croatia. Then in 1964 he worked with George Nelson on the Chrysler Pavilion for the World’s Fair in Queens, New York. There the objective was to educate children about the automotive industry, and in the course of designing safety posters, Wyman created a series of whimsical pictograms that would later be widely used in factories across the United States.

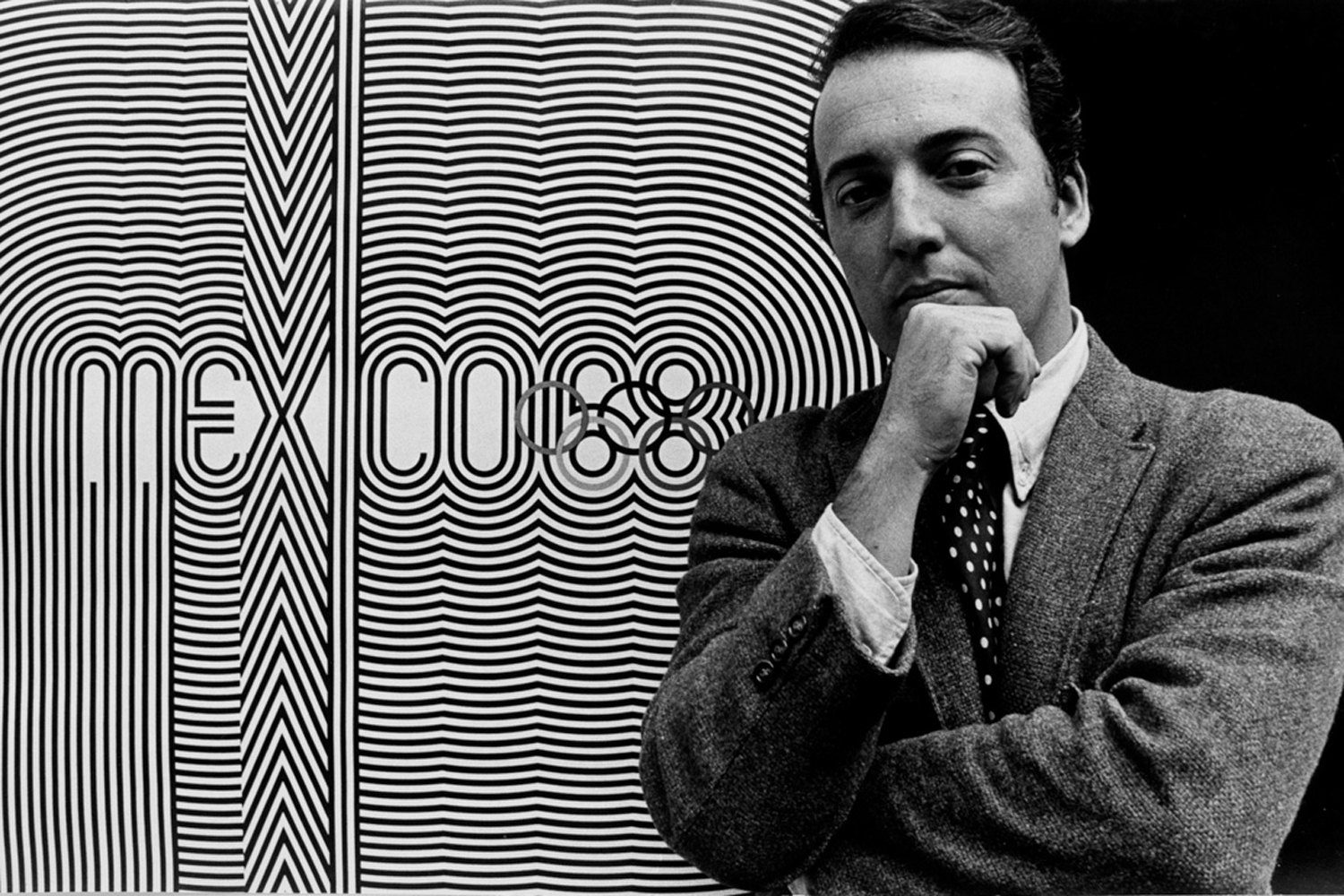

Wyman’s ability to condense information into precise and easily understood motifs found its purest essence in Mexico City, which inspired his logos for the Camino Real Hotel, the Mexico City Metro, and the 1970 World Cup. When he traveled there to pitch a system of graphics for the 1968 Olympics, he bought a one-way ticket and spent his first week inside the Museum of Anthropology, soaking in the pre-Columbian cultures of the Aztecs and Mayans. “I had no idea about Mexico,” he says. “All I knew was that they had piñatas.”

His eventual design—weaving in Op Art abstraction and vibrating colors with geometric forms of Mexican folk art—ended up being reproduced not just on brochures but on the sides of buildings, uniforms, stamps, public installations, and homemade signs. The logo elegantly combined the numbers six and eight with the game’s signature rings in a way that referenced the country’s visual history without appropriating or patronizing local culture. His sophisticated icons served as a common visual language for an audience who, largely, was not fluent in Spanish.

The identity for the XIX Olympic Games has become the prototype for how designers can respond to a particular time and place in a public and accessible way. In Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, Philip B. Meggs calls the design for the games “one of the most successful in the evolution of visual identification.” Wyman’s design for the Mexico City Metro refined his approach further. Each station is identified by a meaningful icon—a visual mnemonic—that draws on an anecdote from history, an existing monument in the area, or an important function related to that neighborhood. He came up with the image of the grasshopper for Chapultepec station because in the Aztec language, Chapultepec means “grasshopper hill.” For Candelaria, an area inhabited by criminals known as “ducks” in the local slang, the station logo depicts a swimming duck. His emphasis on pictograms would influence the designers of the smartphone and the app store 40 years later.

Today Wyman still works out of a his studio on the Upper West Side, where he and his wife, Neila, have lived since 1971. He spent 40 years at Parsons teaching the next generations of students, and he has always worked with small teams, preferring to remain close to actual design work.

Spanning cities all over the globe, Wyman has leveraged his unique ability to transform two-dimensional marks into a visual language that can communicate in a three-dimensional real world. This ability to help people move freely from place to place is what—more than anything—will remain his greatest contribution. “I just wanted to make something that wouldn’t disappear.”

And that’s exactly what he did.

Hope you might join us at our studios in Greenwich Village.